Ce guide est destiné aux lecteurs qui cherchent à comprendre la guerre au Soudan, en particulier à ceux qui ont peu ou pas de connaissances préalables. Si vous le trouvez utile, pensez à le partager pour favoriser une prise de conscience plus large du conflit.

Bref

· Que se passe-t-il? La guerre, la famine, les atrocités, un environnement politique répressif à l’échelle nationale et la plus grande crise de réfugiés au monde.

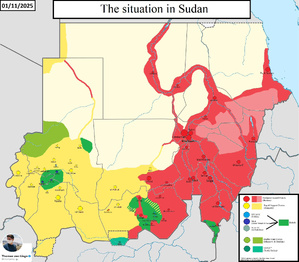

· Où est cette guerre ? Le Soudan était autrefois le plus grand pays d’Afrique, jusqu’à l’indépendance du Soudan du Sud en 2011. Les combats ont commencé dans la capitale, Khartoum, en 2023, se sont intensifiés le long de la vallée du Nil en 2024 et se sont déplacés vers l’ouest en direction des régions arides du Darfour et du Kordofan en 2025.

· Qui se bat ?

o Forces armées soudanaises (SAF) — L’armée nationale, façonnée par des décennies de régime autoritaire et maintenant contrôlée par une junte militaire.

o Forces de soutien rapide (RSF) — Une coalition de milices arabes soudanaises (souvent décrites comme paramilitaires) originaire du Darfour et du Kordofan occidental. Autrefois alignées sur l’armée, les RSF sont devenues puissantes de manière indépendante et se sont mutinées en 2023, déclenchant la guerre civile.

· Pourquoi se battent-ils ? Les motivations comprennent le pouvoir, l’argent, l’idéologie, le nationalisme et la haine ethnique. Il y a aussi la logique interne d’une guerre prolongée : des années de combats, d’atrocités massives et de lourdes pertes des deux côtés ont alimenté un cycle de vengeance et d’appels ouverts à l’extermination de l’ennemi. Même les Soudanais, qui veulent désespérément que la guerre se termine, ont du mal à imaginer à quoi pourrait ressembler la paix ou la coexistence.

· The Outside Backers:

o Egypt and Turkey are key supporters of the Sudanese military, providing both political backing and practical assistance. Iran also supplied the SAF with weapons, though its support has ended.

o The United Arab Emirates (UAE) is the leading supplier of the RSF, providing attack drones, armored cars, medical treatment for wounded combatants, and financing entire mercenary units .

o Chad has played a more passive but still critical role by allowing RSF rear-area operations on its territory, including recruitment, military logistics, and economic activities. Kenya, while officially neutral, has permitted the RSF to conduct political organizing within its borders.

Mother Hawa holds her son Waleed in a temporary shelter in Tawila, North Darfur, April 2025. Waleed was admitted in the hospital in Zamzam when the hospital was hit by artillery. While many were killed, Hawa was able to flee to Tawila with her son and the other two children. (Mohammed Jamal/UNICEF)

The Warring Parties: An Overview

Sudan’s war is primarily a struggle between two major armed groups, the SAF and the RSF. Smaller factions play a secondary but still significant role.

Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF): “One People, One Army”

The national military, commanded by General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, controls most of northern, central, and eastern Sudan from its base in Port Sudan. The SAF portrays itself as the guardian of national unity and state authority—defending the country from collapse and disorder. Though it lacks a democratic mandate, Sudan’s military regime argues for its legitimacy on the basis of necessity and national crisis.

SAF is numerically superior to the RSF and relies more on defensive tactics, fixed positional warfare, aerial bombing, and limited, carefully planned offensive operations. SAF has proved itself more capable than the RSF in long-term urban combat environments, but it has struggled with maneuver, tactical flexibility, and long-distance logistics in remote rural areas.

SAF consists of the Army, Air Force, and Navy. It is supported by several paramilitaries, including the Central Reserve Police, Sudan Shield, the Operations Authority of the General Intelligence Service, and the Al-Baraa Ibn Malik Brigade (an unofficial but powerful Islamist paramilitary). Additionally, SAF has relied on contracted mercenary aviation assets.

Understand the war. Shine a light on Sudan’s crisis. Subscribe to support Sudan War Monitor.

Rapid Support Forces (RSF): “Victory or Death”

Combattant d’une milice arabe, affiliée aux RSF, avec des prisonniers à Ardamata, dans l’ouest du Darfour, novembre 2023.

Les RSF sont des paramilitaires créés par un ancien dictateur (Omar el-Béchir) pour aider à réprimer les rébellions dans la région occidentale du Darfour et dans les monts Nouba du Kordofan du Sud.

Le gouvernement d’Al-Bashir a constitué les RSF à partir de milices locales recrutées parmi les tribus pastorales du Darfour et du Kordofan qui s’identifient comme arabes, notamment les Rizeigat, les Misseriya, les Beni Halba, les Salamat et les Ta’isha. Familièrement appelées les « Janjawids », ces milices ont été impliquées dans des violences génocidaires contre les tribus non arabes du Darfour au début des années 2000. Ils ont joué un rôle central dans la défaite militaire des groupes rebelles du Darfour.

Initialement, le régime de Béchir a armé et payé secrètement les milices janjawids par l’intermédiaire du service de renseignement militaire. Cependant, les RSF ont acquis un statut légal en tant que paramilitaires nationaux en 2014. Par la suite, les RSF ont gagné en taille et en puissance, alors même que les conflits au Darfour et au Kordofan s’apaisaient. Ils ont combattu en tant que mercenaires au Yémen pour les Émirats arabes unis, ainsi qu’en Libye.

Les RSF sont dirigées par Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, un chef de milice Rizeigat de longue date issu d’un milieu d’éleveurs de chameaux.

Les RSF préfèrent la guerre de manœuvre, en envoyant leurs troupes dans des pick-up modifiés avec des canons lourds (« technicals ») et des voitures blindées. De plus, ils utilisent des drones d’attaque pour la surveillance, les attaques stratégiques à longue portée et les opérations de combat urbain. Les RSF se financent grâce à la contrebande, à l’extraction d’or, à l’extorsion, au pillage et au soutien extérieur des Émirats arabes unis.

Together with allied political groups, the RSF formed a political alliance, known as Ta’sis (Establishment/Founding), which has declared the creation of a rival government to administer territory under RSF control. Known as the Government of Peace and National Unity, this entity has not achieved any international recognition.

Allied and Neutral Groups

Map by OSINT researcher Thomas van Linge . The lines of control are approximate and fluid/unclear in some areas.

Several rebel and non-aligned armed groups were already active in Sudan prior to the outbreak of the current war. Each group has its own command structure, ethnic base, and foreign ties.

· Joint Force of Armed Struggle Movements (JFASM): A coalition of Darfur rebel groups that signed the 2020 Juba Peace Agreement, led by Minni Arko Minnawi. The Joint Force stayed neutral for the first year of the war before declaring war on the RSF and allying with SAF in early 2024. It played a central role in the 18-month siege of El Fasher, repulsing dozens of RSF attacks, until the eventual fall of the city in October 2025. The Joint Force consists of two main groups, JEM and SLM-Minawi, plus a handful of small factions. The majority of its forces are ethnic Zaghawa.

· Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N): Led by Abdel Aziz al-Hilu, the SPLM-North historically had close ties politically and militarily with the guerrilla movement that became the ruling party of South Sudan (SPLM). It controls the Nuba Mountains and consists mostly of ethnic Nuba, a term for a variety of non-Arab tribes of South Kordofan State. SPLM-N formed an alliance with the RSF in early 2025 and is currently besieging the cities of Kadugli and Dilling.

SPLM-N soldiers, South Kordofan

· Sudan Liberation Movement/Army (SLA-AW): Led by long-time exile Abdelwahid Al-Nur, this faction controls the Jebel Marra highlands of central Darfur. It is neutral in the war and its territory has served as a safe haven for thousands of people fleeing from elsewhere in Darfur. Its leadership and the majority of its soldiers are ethnic Fur.

· Sudan Liberation Movement – Transitional Council (SLM-TC): Led by Al-Hadi Idriss and active in North Darfur, this group initially stayed neutral before splitting, with some men joining SAF and others joining the Ta’sis Alliance led by the RSF.

Who is Winning the War?

Nobody is winning. The country as a whole is losing.

Throughout the conflict, both sides have claimed to have the upper hand and predicted imminent total victory. Consistently, these predictions have turned out to be false, as the tides of war have ebbed and flowed.

For the first year and half of the war (April 2023-August 2024), the RSF defeated SAF many times in battle, seizing vast territories in western and central Sudan and taking control of most of the capital. The launch of a multi-front SAF counteroffensive in September 2024 culminated in the recapture of Khartoum and its sister city Omdurman by May 2025.

SAF fighters in front of the Republican Palace in March 2025, after its recapture from the RSF.

SAF’s momentum waned in mid-2025 as the war shifted closer to the RSF’s strongholds in Darfur and West Kordofan. In the meantime, the RSF intensified its siege of El Fasher, the final SAF-held city in Darfur, and employed new long-range drones to attack critical targets, both civilian and military, undermining morale and public trust in the Sudanese military.

Smoke from burning vehicles after combat in Sheikan Locality, North Kordofan State, August 2025

The fall of El Fasher in October 2025, following an 18-month siege, marked a major setback for SAF. Subsequently, the RSF also attacked a SAF garrison in Babanusa, West Kordofan. Overall, the conflict appears to be a stalemate, though each side continues to search for ways to gain the upper hand.

Understand the war. Shine a light on Sudan’s crisis. Subscribe to support Sudan War Monitor.

Why Are They Fighting?

RSF leader Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo

Economic, ideological, environmental, and international factors are major causes of Sudan’s ongoing war. Less often discussed is the conflict’s significant ethnic dimension. Most of the RSF are nomadic Arabs from Darfur and Kordofan, whereas the leadership of the SAF are mostly Nile Valley Arabs from cities and farming areas.

Central and eastern Sudan, the stronghold of the Sudanese military, is more developed economically and enjoyed relative peace prior to 2023. By contrast, Darfur and Kordofan are poorer, rural, and historically more violent. The RSF rank-and-file were shaped by decades of local conflict, which resulted in a warrior ethos that glorifies violence and denigrates peacetime occupations such as farming, business, and education.

Historically, Sudan’s Nile Valley Arabs held the highest rung within an established racial hierarchy. This system developed during the Turco-Egyptian and British colonial eras, before becoming entrenched after independence in 1956. It placed darker skinned Nuba, Ingessana, South Sudanese, Masalit, Fur and other non-Arab tribes at the bottom of the hierarchy. Collectively, these groups were referred to as “slaves.”

The pastoralist Arab tribes of Darfur and Kordofan, which form the core of the RSF, held a middle rank within Sudan’s historical racial hierarchy. As they grew in power in recent decades, they began to challenge the privileged position of the Nile Valley Arabs within the historical racial hierarchy. Today, RSF propagandists often denigrate Sudan’s northerners as impure (racially mixed), cowardly, and tools of the former colonial masters.

The ethnic dimensions of the conflict are not as straightforward as they were in certain other contexts, such as Rwanda in 1994. Sudan is more diverse and neither warring party is ethnically monolithic. Nevertheless, long-standing racial attitudes remain ever-present in the background of the conflict, if not always openly discussed. Both sides have carried out mass arrests and extrajudicial killings on an ethnic basis.

Sudan War Monitor publishes 2-4 weekly updates about the conflict, including news, analysis, videos, maps, political context, and updates about the humanitarian situation.

How Many People Have Died?

A group of boys helped dig a mass grave in Mayo District, Khartoum, after an airstrike that killed at least 43 civilians, September 2023.

There are no reliable estimates. Civilian deaths are sometimes counted and documented, but the warring parties do not disclose their losses.

Conservatively, we estimate that at least 100,000 people have died in the conflict, though a higher toll of 150,000-200,000 is also a reasonable estimate. These figures refer only to direct conflict deaths, not excess mortality caused by conflict indirectly, such as deaths caused by malnutrition or disease outbreaks that otherwise would not have occurred.

A mortality study by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine estimated that over 61,000 people died of all causes in Khartoum State between April 2023 and June 2024, a 50% increase in the pre-war death rate. Of these, 26,024 deaths were due to intentional injuries. And that figure covers only one state and only the first 14 months of the war.

Woman and child in eastern Sudan in 2024. Many war-displaced people now live in tents, abandoned schools, or with relatives.

Both sides have committed atrocities against civilians as well as war crimes including executing prisoners of war and deliberate targeting of civilian markets. Many civilians have died as a result of indiscriminate aerial bombing and shelling, as well as targeted aerial attacks (launched by drones or airplanes) on civilian targets — including markets, mosques, and hospitals.

Cholera patients in Sudan, 2025

What Are the Economic Consequences?

Sudan’s gross domestic product contracted by approximately 29.4% in 2023 and another 13.5% in 2024, according to World Bank data. Inflation soared by 66% in 2023 and another 170% in 2024, as the currency collapsed.

La production céréalière nationale (sorgho, blé et millet) a chuté de plus de 40 % au cours de la première année de la guerre, selon l’Organisation des Nations Unies pour l’alimentation et l’agriculture. La famine s’est emparée de plusieurs régions du Darfour et du Kordofan, les services de base se sont effondrés et de nombreux marchés sont fermés ou détruits. Les épidémies, y compris le choléra, ont augmenté parmi les communautés déplacées.

Incendies d’entrepôts à l’extérieur d’Omdurman, 2023

Deux ans de combats urbains ont dévasté la capitale du pays, Khartoum, et plusieurs autres villes. Cela a gravement endommagé le secteur industriel, le secteur gouvernemental et le secteur financier, et a poussé des millions de personnes à fuir leurs foyers, créant une profonde crise économique. Environ 71 % de la population vit avec moins de 2,15 dollars par jour, soit plus du double du taux de pauvreté d’avant-guerre.

Des femmes et des enfants lors d’un dépistage de la malnutrition à Rokoro, dans le Darfour-Centre, septembre 2024

La troisième année de la guerre s’est principalement déroulée dans les zones rurales, les petites villes et la ville d’El Fasher, dans l’ouest du pays. Bien que cela ait permis aux Soudanais des villes de rentrer chez eux dans certaines régions, l’économie nationale reste en difficulté en raison de l’inflation, de la militarisation et des dommages durables causés aux institutions économiques nationales et aux infrastructures essentielles comme les ponts et les réseaux électriques. En outre, la confiance des investisseurs et des entreprises s’est effondrée, ce qui signifie qu’il est peu probable que l’activité économique redémarre, même dans les zones où les conflits se sont apaisés.

Entre-temps, les rangs des deux parties belligérantes se sont gonflés en raison du recrutement forcé, du chômage généralisé et de la fermeture des écoles et des universités (les deux camps emploient des soldats adolescents). On estime que 19 millions d’enfants soudanais ne sont pas scolarisés.

Damaged hospital in East Nile, Khartoum State

When and How Did the Conflict Start?

The RSF mutinied in April 2023. They stormed the presidential palace, military airfields, and other key government sites. For this reason, critics say the RSF attempted a coup, which failed, triggering a prolonged fight for power and survival. However, the RSF counters that it was attacked first.

Both sides appear to have prepared in advance for the conflict. For background, political tensions between the SAF and the RSF began building in 2022. Each side began reinforcing its troops in the capital, resulting in growing distrust between the two sides. On April 15, 2023, fighting erupted suddenly in Khartoum, and spread quickly to other areas. Both sides claim that the other side fired the first shot.

What Kind of Government Does Sudan Have?

Admiral Ibrahim Jaber (right) and Lt Gen. Shams ad-Din Kabbashi (left), two senior members of Sudan’s military government.

Sudan’s national government is controlled by a military junta, known as the “Sovereignty Council,” which took power in a coup in 2021, overthrowing the interim civilian government of Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok.

This coup accelerated the political breakdown leading to the current war. Despite this, SAF presents itself as the only force capable of maintaining order during a time of national emergency.

Many of Sudan’s generals are holdovers from the Islamist regime of Omar al-Bashir, who ruled from 1989-2019. Sudan has a civilian prime minister and cabinet appointed by the nation’s military ruler. It has no parliament. Though nominally a federal system, political power in reality is centralized, with state governments being largely or wholly dependent on the national government.

Wreckage of a drone shot down near El Obeid, 8 Nov 2025

Is This a Religious Conflict?

The short answer: No, Sudan’s war is not a religious war in the usual sense of that phrase. Approximately 90% of Sudanese practice the Islamic faith or are nominally Muslim, and most soldiers on both sides of the conflict identify as Muslims. Non-religious persons, Christians, and believers in indigenous religions constitute small minorities in Sudan.

This war should not be confused with the Second Sudanese Civil War (1983-2005), which was sometimes framed as a religious conflict because it was fought largely in South Sudan, which has a substantial Christian population.

The more nuanced answer: Religion is an important part of life in Sudan, and religious ideology and language is used by leaders on both sides to motivate soldiers, justify the violence, and console the grieving. Additionally, the religio-political ideology of the longtime ruling party, the National Islamic Front (aka National Congress Party), has influenced many officers of the Sudanese military, and plays a role in driving the conflict, according to secular Sudanese political parties opposed to the war.

The RSF claim to be fighting to rid the country of the “remnants” of this former Islamist regime, though the RSF itself was created to defend the former regime. Critics see the RSF’s anti-Islamist stance as a tactical one, designed to attract support in the Middle East, particularly from the UAE, which is a liberal Gulf monarchy that opposes Islamist political forces.

How is South Sudan Involved or Affected?

Sudan (orange) and South Sudan (green) have both suffered civil wars.

South Sudan isn’t directly involved in Sudan’s war, though various armed groups have used its territory as a safe haven and staging area, including SAF, RSF, and SPLM-N. The neutrality of South Sudan, its instability, and the nation’s culture of rampant corruption make it an important contested area for covert operations, including smuggling weapons and looted goods, evacuation of wounded combatants, repatriation of escapees from captured or besieged areas, influence operations and mercenary recruitment, etc.

South Sudan itself is deeply affected by Sudan’s war, despite its neutrality. It achieved its independence from Sudan in 2011 but it still has close economic and social ties with Sudan. It fought its own internal civil war from 2013 to 2018, leaving lasting social and economic scars.

Oil exports via pipelines in Sudan are South Sudan’s main source of GDP and government income. For about a year, the war interrupted these exports, due to damage to pipelines and the disruption of critical maintenance operations. Although exports have resumed, the severe and prolonged loss of government revenues has destabilized South Sudan’s already fragile government and amplified existing political and military tensions.

How is the War Related to the Massive Protests in Sudan a Few Years Ago?

Photo by Yusuf Yassir on Unsplash

Sudan enjoyed a period of relative peace from 2019-2023, after the Sudanese Revolution. That was a popular uprising that started in December 2018, leading to the toppling of the long-time dictator Omar al-Bashir.

Millions of pro-democracy protesters took to the streets, demanding civil rights and a more peaceful future. After months of mass protests, in April 2019 the military ousted al-Bashir, and partly turned over power to a civilian government, headed by a civilian prime minister. This civilian-led government had plans for elections and security sector reform. They made peace with some Darfur and Blue Nile rebel groups, and they put the former dictator and some of his henchmen on trial.

However, the military never fully relinquished power, and in October 2021 they carried out a counter-revolutionary coup d’état, ousting the civilian component of the government. After that, the army ruled the country in partnership with its paramilitary ally, the RSF, until the two armed services turned on each other. Unfortunately, the rivalry and ambitions of these two groups has shattered the hopes of the pro-democracy protesters.

Get more from Sudan War Monitor in the Substack app

Available for iOS and Android

Decades of War: What’s Different This Time?

Sudan has a complex history that involves a series of different conflicts, but also periods of relative peace. Depending how one counts, this is Sudan’s fifth civil war since independence in 1956. The previous wars include:

· First Sudanese Civil War (Anyanya War): 1955-1972

· Second Sudanese Civil War (SPLM War): 1983-2005

· Darfur War: 2003 - 2019

· SPLM-North War (Nuba Mountains and Blue Nile): 2011-2019

Historians and analysts see recurring drivers across these conflicts—economic marginalization, political exclusion, ethnic hierarchy—but also important differences. For example, the first two civil wars featured strong separatist movements, whereas the current war does not involve any separatist factions.

Another key difference is that all of the prior wars were fought in Sudan’s hinterlands. This war, by contrast, erupted in the capital Khartoum and involved sustained fighting in the nation’s Nile Valley heartland.

Urban warfare in Khartoum and its sister cities, Bahri and Omdurman—together one of Africa’s largest metropolitan areas—produced mass displacement on a scale unprecedented in Sudan’s history.

Finally, this war carries a greater risk of state collapse than any previous conflict. The RSF rebellion in 2023 marked a defining moment in Sudanese history. At one point in 2024, the RSF controlled most of Khartoum and Omdurman as well as the fertile states of Al Jazeera and Sennar, and appeared poised to topple the government. Though they have since retreated westward, the RSF remain a potent threat.

What Is Being Done to Stop Sudan’s War?

Short answer: not much.

Pleins feux sur la crise au Soudan

Sudan War Monitor se consacre au suivi de la plus grande crise humanitaire au monde et du conflit qui l’a provoquée. Nous avons été en mesure de soutenir et de développer cette initiative grâce à un réseau mondial de sympathisants. Vous pouvez aider en passant à un abonnement payant , qui vous donne accès à des extras réservés aux abonnés, ainsi qu’à notre archive complète de rapports et d’analyses.

Autres façons d’aider :

📢 Transmettez nos bulletins d’information à vos collègues et amis.

📲 Partagez notre travail sur les réseaux sociaux.

🔗 Lien vers Sudan War Monitor depuis votre site Web ou votre blog.

🎁 Achetez un abonnement cadeau pour quelqu’un d’autre.

💳 Faites un don unique .

✍️ Laissez un commentaire ou un témoignage réfléchi.

1. "Nous détenons toutes les preuves du soutien émirati à la milice de Hemedti", L’ambassadeur du Soudan en Turquie

2. Strategic Dialogue Between Egypt and the United States on African Affairs, with a Focus on Sudan

3. Strategic Dialogue Between Egypt and the United States on African Affairs, with a Focus on Sudan

4. Sudan: Population Displacement Intensifies as Humanitarian Infrastructure Collapses

5. السودان: تزايد حركة النزوح وانهيار البنية التحتية الإنسانية الأحد 2 نوفمبر

6. El-Fasher : fracture régionale et recomposition du pouvoir au Tchad (mis à jour)

7. Aucun crime ne saurait être excusé par les crimes commis par le camp adverse.

8. Soudan: les appels au boycott des Émirats arabes unis se multiplient après la prise d'El-Fasher par les FSR

9. Crimes des Forces de soutien rapide – Rapport du Yale Humanitarian Research Lab